Lester B. Pearson

| The Right Honourable Lester Bowles Pearson PC CC OBE OM MA (Oxon) |

|

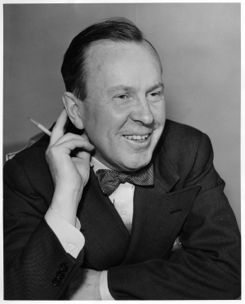

Lester B. Pearson, 1944 |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 22 April 1963 – 20 April 1968 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | John Diefenbaker |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Trudeau |

|

Leader of the Opposition

|

|

| In office January 16, 1958 – April 21, 1963 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | Louis St. Laurent |

| Succeeded by | John Diefenbaker |

|

8th Secretary of State for External Affairs

|

|

| In office September 10, 1948 – June 20, 1957 |

|

| Prime Minister | William Lyon Mackenzie King |

| Preceded by | Louis St. Laurent |

| Succeeded by | John Diefenbaker |

|

2nd Canadian Ambassador to the United States

|

|

| In office 1944–1946 |

|

| Prime Minister | William Lyon Mackenzie King |

| Preceded by | Leighton McCarthy |

| Succeeded by | H. H. Wrong |

|

8th President of the United Nations General Assembly

|

|

| In office 1952 |

|

| Preceded by | Luis Padilla Nervo |

| Succeeded by | Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit |

|

Member of the Canadian Parliament

for Algoma East |

|

| In office 25 October 1948 – 23 April 1968 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Farquhar |

| Succeeded by | None (district abolished) |

|

|

|

| Born | April 23, 1897 Newtonbrook, Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | December 27, 1972 (aged 75) Ottawa, Ontario |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) | Maryon Pearson |

| Children | Geoffrey, Patricia |

| Alma mater | University of Toronto (B.A.) University of Oxford (B.A.) University of Oxford (M.A.) |

| Profession | Soldier, Diplomat, Academic, Historian |

| Religion | Methodist, then United Church of Canada |

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize (1957) |

| Signature | |

Lester Bowles "Mike" Pearson, PC, OM, CC, OBE (23 April 1897 – 27 December 1972) was a Canadian professor, historian, civil servant, statesman, diplomat, and politician, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for organizing the United Nations Emergency Force to resolve the Suez Canal Crisis. He was the 14th Prime Minister of Canada from 22 April 1963, until 20 April 1968, as the head of two back-to-back minority governments following elections in 1963 and 1965.

During Pearson's time as Prime Minister, his minority government introduced universal health care, student loans, the Canada Pension Plan, the Order of Canada, and the current Canadian flag. During his tenure, Prime Minister Pearson also convened the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. With these accomplishments, together with his groundbreaking work at the United Nations and in international diplomacy, Pearson is generally considered among the most influential Canadians of the 20th century.

Contents |

Early years

Pearson was born in Newtonbrook, Toronto, the son of Edwin Arthur Pearson, a Methodist (later United Church of Canada) minister and Anne Sarah Bowles. He graduated from Hamilton Collegiate Institute in Hamilton, Ontario in 1913 at the age of 16. Later that same year, he entered Victoria College at the University of Toronto,[1] where he lived in residence in Gate House and shared a room with his brother Duke. While at the University of Toronto, he joined the Delta Upsilon Fraternity. He was subsequently elected to the Pi Gamma Mu social science honour society's chapter at the University of Toronto for his outstanding scholastic performance in history and sociology.

Outstanding sportsman

At U of T, he became a noted athlete, excelling in rugby union, and also playing basketball. He later also played for the Oxford University Ice Hockey Club while on a scholarship at the University of Oxford, a team that won the first-ever Spengler Cup in 1923. Pearson also excelled in baseball and lacrosse as a youth, played golf and tennis as an adult, and as a result had the most intense and wide-ranging sporting interests of any Canadian prime minister. His baseball talents were sufficient enough for a summer of semi-pro play with the Guelph Maple Leafs of the Ontario Intercounty Baseball League.[2]

First World War

When the First World War broke out in 1914, he volunteered for service as a Medical Orderly with the University of Toronto Hospital Unit. In 1915, he undertook overseas service with the Canadian Army Medical Corps as a stretcher bearer with the rank of Private, and had a subsequent commissioning to the rank of Lieutenant. During this period of service he spent two years in Egypt and Greece. In 1917, Pearson transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (as the Royal Canadian Air Force did not exist at that time), where he served as a Flying Officer until being sent home with injuries from two accidents; while training as a pilot at an air training school in Hendon, England, Pearson survived an airplane crash during his first flight. Unfortunately, in 1918, he was hit by a London bus during a blackout and was sent home as an invalid to recuperate, and was then discharged from the service. It was as a pilot that he received the nickname of "Mike", given to him by a flight instructor who felt that "Lester" was too mild a name for an airman. Thereafter, Pearson would use the name "Lester" on official documents and in public life, but was always addressed as "Mike" by friends and family.[3]

Interwar years

After the war, he returned to school, receiving his BA from the University of Toronto in 1919; he was able to complete his degree after one more term, under a ruling in force at the time, since he had served in the military during the war. He then spent a year working in Hamilton and Chicago, in the meat-packing industry, which he did not enjoy. Upon receiving a scholarship from the Massey Foundation, he studied for two years at St John's College at the University of Oxford, where he received a BA with Second-Class honours in modern history in 1923, and the MA in 1925. After Oxford, he returned to Canada and taught history at the University of Toronto, where he also coached the Varsity Blues Canadian football team, and the Varsity Blues men's ice hockey team. In 1925, he married Maryon Moody (1901–1989), who was one of his students at the University of Toronto. Together, they had one daughter, Patricia, and one son, Geoffrey.[4]

Diplomat

In 1927, after scoring the top marks on the Canadian foreign service entry exam, he then embarked on a career in the Department of External Affairs.[2] Pearson was posted to London in the late 1930s, and served there as World War II began in 1939, until 1942 as the second-in-command at Canada House, where he coordinated military supply and refugee issues, serving under High Commissioner Vincent Massey.[2] Pearson returned to Ottawa for a few months. He was assistant under secretary in Ottawa from 1941 until 1942.[5] In June 1942 he was posted to the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C. as ministerial counsellor.[5] He served as second-in-command for nearly two years. Promoted minister plenipotentiary, 1944, he became Canada's ambassador to the United States on January 1, 1945, until September 1946.[2][6] He had an important part in founding both the United Nations and NATO.[7] During the Second World War, he once served as a courier with the codename "Mike." He went on to become the first director of Signal Intelligence.

Pearson nearly became the first secretary-general of the United Nations in 1945, but this possibility was vetoed by the Soviet Union.[8]

Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King tried to recruit Pearson into his government as the war wound down. Pearson felt honoured by King's approach, but resisted at the time, due to his personal dislike of King's interpersonal style and political methods.[9] Pearson would not make the move into politics until a few years later, after King had announced his retirement as prime minister.

Early political career

In 1948, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent appointed Pearson Minister of External Affairs in the Liberal government. Shortly afterward, he won a seat in the Canadian House of Commons, for the federal riding of Algoma East.

Wins Nobel Peace Prize

In 1957, for his role in defusing the Suez Crisis through the United Nations, Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The selection committee claimed that Pearson had "saved the world." The United Nations Emergency Force was Pearson's creation, and he is considered the father of the modern concept of peacekeeping. Leaders of the United States, France, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain (for best example) all had vested interests in the natural resources around the Suez Canal. Pearson was able to organize these leaders by way of a five-day fly-around, and was by effect responsible for the development of the structure for the United Nations Security Council. His Nobel medal is on permanent display in the front lobby of the Lester B. Pearson Building, the headquarters of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade in Ottawa.

Party leadership

After the resignation of Louis St. Laurent, Pearson was elected leader of the Liberal Party at its 1958 leadership convention, defeating his chief rival, cabinet minister Paul Joseph James Martin.

As the newly-elected leader of the Liberals, Mr. Pearson had given an ill-advised speech in the House of Commons that asked Prime Minister John Diefenbaker to give power back to the Liberals without an election, because of a recent economic downturn. This strategy backfired when Diefenbaker seized on the error by showing a classified Liberal document saying that the economy would face a downturn in that year. This contrasted heavily with the Liberal's 1957 campaign promises.

Consequently, Pearson's party was badly routed in the election of that year, losing over half their seats, while Diefenbaker's Conservatives won the largest majority ever seen in Canada to that point (208 of 265 seats). The election also cost the Liberals their Quebec stronghold; the province had voted largely Liberal in federal elections since the Conscription Crisis of 1917, but upon the resignation of former Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, the province had no favourite son leader, as they had had since 1948.

Pearson convened a significant 'Thinkers' Conference' at Kingston, Ontario in 1960, which developed many of the ideas later implemented when he became prime minister.[10]

In the 1962 election, his party reduced the Progressive Conservative Party of John Diefenbaker to a minority government.

Not long after the election, Pearson capitalized on the Conservatives' indecision on installing nuclear warheads on Bomarc missiles. Minister of National Defence Douglas Harkness resigned from Cabinet on 4 February 1963, because of Diefenbaker's opposition to accepting the missiles. The next day, the government lost two non-confidence motions on the issue, prompting the election.

Prime minister

Pearson led the Liberals to a minority government in the 1963 general election, and became prime minister. He had campaigned during the election promising "60 Days of Decision" and support for the Bomarc missile program.

Pearson never had a majority in the Canadian House of Commons, but he nevertheless managed to bring in many of Canada's major social programs, including universal health care, the Canada Pension Plan and Canada Student Loans, and established a new national flag, the Maple Leaf. This was due in part to support for his minority government in the House of Commons from the New Democratic Party, led by Tommy Douglas. His legislation included instituting the 40-hour work week, two weeks vacation time and a new minimum wage.

Pearson signed the Canada-United States Automotive Agreement (or Auto Pact) in January 1965, and unemployment fell to its lowest rate in over a decade.[11] While in office, Pearson declined U.S. requests to send Canadian combat troops into the Vietnam War. Pearson spoke at Temple University in Philadelphia on 2 April 1965, while visiting the United States and voiced his support for a pause in the American bombing of North Vietnam, so that a diplomatic solution to the crisis may unfold. To the Johnson administration, this criticism of American foreign policy on US soil was an intolerable sin. Before Pearson had finished his speech, he was summoned to Camp David to meet with Johnson the next day. Johnson, who was notorious for his personal touch in politics, reportedly grabbed Pearson by the lapels and shouted, "Don't you come into my living room and piss on my rug."[12][13] Pearson later recounted that the meeting was acrimonious, but insisted the two parted cordially. After this incident, LBJ and Pearson did have further contacts, including two further meetings together, both times in Canada (the country would profit immensely from the Vietnam War, through increased sales of the raw materials and resources that would fuel and sustain the U.S. military machine).[14] Elderly Canadians often remember the Pearson years as a time Canada-U.S. relations greatly improved.[15]

Pearson also started a number of Royal Commissions, including one on the status of women and another on bilingualism. They instituted changes that helped create legal equality for women, and brought official bilingualism into being. After Pearson, French was made an official language, and the Canadian government would provide services in both. Pearson himself had hoped that he would be the last unilingual Prime Minister of Canada and, indeed, fluency in both English and French became an unofficial requirement for Prime Ministerial candidates after Pearson left office.

His government endured significant controversy in Canada's military services throughout the mid-1960s, following the tabling of the White Paper on Defence in March 1964. This document laid out a plan to merge the Royal Canadian Navy, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Canadian Army to form a single service called the Canadian Armed Forces. Military unification took effect on 1 February 1968, when The Canadian Forces Reorganization Act received Royal Assent.

Pearson was also remarkable for instituting the world's first race-free immigration system, throwing out previous ones that had discriminated against certain people, such as Jews and the Chinese. His points-based system encouraged immigration to Canada, and a similar system is still in place today.

Pearson also oversaw Canada's centennial celebrations in 1967 before retiring. The Canadian news agency, The Canadian Press, named him "Newsmaker of the Year" that year, citing his leadership during the centennial celebrations, which brought the Centennial Flame to Parliament Hill.

Also in 1967, the President of France, Charles de Gaulle made a visit to Quebec. During that visit, de Gaulle was a staunch advocate of Quebec separatism, even going so far as to say that his procession in Montreal reminded him of his return to Paris after it was freed from the Nazis during the Second World War. President de Gaulle also gave his "Vive le Québec libre" speech during the visit. Given Canada's efforts in aid of France during both world wars, Pearson was enraged. He rebuked de Gaulle in a speech the following day, remarking that "Canadians do not need to be liberated" and making it clear that de Gaulle was no longer welcome in Canada. The French President returned to his home country and would never visit Canada again. Nevertheless, with the rise of French-Canadian nationalism in Quebec, the Pearson government would give influential francophone Liberals (but not without them giving the utmost loyalty to the British Crown), who decried so-called English-speaking domination, more power in Ottawa and the federal bureaucracy.

Supreme Court appointments

Pearson chose the following jurists to be appointed as justices of the Supreme Court of Canada by the Governor General:

- Robert Taschereau (as Chief Justice, 22 April 1963 – 1 September 1967; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister King, 9 February 1940)

- Wishart Flett Spence (30 May 1963 – 29 December 1978)

- John Robert Cartwright (as Chief Justice, 1 September 1967 – 23 March 1970; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister St. Laurent, 22 December 1949)

- Louis-Philippe Pigeon (21 September 1967 – 8 February 1980)

Retirement

After his announcement on 14 December 1967, that he was retiring from politics, a leadership convention was held. Pearson's successor was Pierre Trudeau, whom Pearson had recruited and made Minister of Justice in his cabinet. Trudeau later became Prime Minister, and two other cabinet ministers Pearson had recruited, John Turner and Jean Chrétien, served as prime ministers in the years following Trudeau's retirement. Paul Martin Jr., the son of Pearson's minister of external affairs, Paul Martin Sr., also went on to become prime minister.

Pearson served as Chairman of the Commission on International Development (the Pearson Commission) which was sponsored by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (The World Bank)from 1968-69. He then served as Chancellor of Carleton University in Ottawa from 1969 until his death in 1972. Pearson is buried just north of Gatineau, in Wakefield, Quebec in Maclaren Cemetery, next to his close External Affairs colleagues H. H. Wrong and Norman Robertson.

Honours and awards

- The Canadian Press named Pearson "Newsmaker of the Year" nine times, a record he held until his successor, Pierre Trudeau, surpassed it in 2000. He was also only one of two prime ministers to have received the honour, both before and when prime minister (the other being Brian Mulroney).

- The award for the best National Hockey League player as voted on by members of the National Hockey League Players' Association (NHLPA) was known as the Lester B. Pearson Award from its inception in 1971 to 2010, when its name was changed to the Ted Lindsay Award to honor one of the union's pioneers.

- Pearson was inducted into the Sports Hall of Fame at the University of Toronto.

- Pearson was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.

- The Lester B. Pearson Building, completed in 1973, is the headquarters for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, a tribute to his service as external affairs minister.

- Lester B. Pearson College, opened in 1974, is a United World College near Victoria, British Columbia.

- The Pearson Medal of Peace, first awarded in 1979, is an award given out annually by the United Nations Association in Canada to recognize an individual Canadian's "contribution to international service."

- Toronto Pearson International Airport, first opened in 1939 and re-christened with its current name in 1984, is Canada's busiest airport.

- The Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, established in 1994, is an independent not-for-profit institution providing research and training on all aspects of peace operations.

- The Lester B. Pearson School Board is the largest English-language school board in Quebec.[16] The majority of the schools of the Lester B. Pearson School Board are located on the western half of the island of Montreal, with a few of its schools located off the island as well.

- Lester B. Pearson High School lists five so-named schools, in Calgary, Toronto, Burlington, Ottawa, and Montreal. There are also elementary schools in Ajax, Ontario; Aurora, Ontario; Brampton, Ontario; London, Ontario; Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; Waterloo, Ontario and Wesleyville, Newfoundland.

- Pearson Avenue is located near Highway 407 and Yonge Street in Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada; less than five miles from his place of birth.

- Pearson Way is an arterial access road located in a new subdivision in Milton, Ontario; many ex-Prime Ministers are being honoured in this growing community, including Prime Ministers Trudeau and Laurier.

- Lester B. Pearson Place completed in 2006, is a four storey affordable housing building in Newtonbrook, Ontario, mere steps from his place of birth.

- Lester B. Pearson Civic Centre,[17] is in Elliot Lake, Ontario

- A plaque at the north end of the North American Life building in North York commemorates his place of birth. The manse where Pearson was born is gone, but a plaque is located at his birth site.[18]

- The Pearson Cup was a baseball competition between the Toronto Blue Jays and Montreal Expos. Pearson also served as Expos' Honorary Club President from 1969-72.

- The Lester B. Pearson Park in St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada

- In a survey by Canadian historians of the first 20 Prime Ministers through Jean Chrétien, Pearson ranked #6. This was used in the book Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders by J.L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer.

Order of Canada Citation

Pearson was appointed a Companion of the Order of Canada on June 28, 1968. His citation reads:[19]

Former Prime Minister of Canada. For his services to Canada at home and abroad.

Honorary degrees

Lester B. Pearson received Honorary Degrees from 48 Universities, including:

- University of Toronto in 1945 (LL.D) [20]

- University of Rochester in 1947 (LL.D)[21]

- McMaster University in 1948 (LL.D)[22]

- Bates College in 1951 (LL.D)[23]

- Princeton University in 1956 (LL.D) [24]

- University of British Columbia in 1958 (LL.D) [25]

- University of Notre Dame in 1963

- Waterloo Lutheran University later changed to Wilfrid Laurier University in 1964 (LL.D)

- Memorial University of Newfoundland in 1964 (LL.D)[26]

- Johns Hopkins University in 1964 (LL.D)[27][28]

- University of Western Ontario in 1964 (LL.D)[29][30]

- Laurentian University in 1965 (LL.D)[31]

- University of Saskatchewan (Regina Campus) later changed to University of Regina in 1965 [32][33]

- McGill University in 1965 [34]

- Queen's University in 1965 (LL.D)[35]

- Dalhousie University in 1967 (LL.D)[36]

- University of Calgary in 1967 [37][38]

- UCSB in 1967

- Harvard University

- Columbia University

- Oxford University (LL.D)

Schools named after LBP

- Lester B. Pearson High School (Calgary) [9]

- Lester B. Pearson College [10]

- Lester B. Pearson Public School (Waterloo, Ontario) [11]

- Lester B. Pearson School, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

- Lester B. Pearson High School, Montreal, Quebec

See also

- List of Prime Ministers of Canada

- Canada and the Vietnam War

- Great Canadian Flag Debate

- Senator Landon Pearson

Notes

- ↑ Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Shadow of Heaven: The Life of Lester Pearson, volume 1, 1897-1948, by John English, 1989.

- ↑ The Nobel Foundation. Lester B. Pearson Biography. Nobelprize.org. Retrieved on: October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Shadow of Heaven: The Life of Lester Pearson, volume 1, 1897-1948, by John English.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Pearson, Lester Bowles", Encyclopedia Canadiana, vol. 8, Ottawa, 1972, Grolier, 135.

- ↑ "Pearson, Lester Bowles," Encyclopedia Canadiana, vol. 8, Ottawa, 1972, Grolier, 135.

- ↑ "He attended many international conferences and was active in the UN from its inception." and "He signed the North Atlantic Treaty for Canada in 1949 and represented his country at subsequent NATO Council meetings, acting as chairman in 1951-1952." See, "Pearson, Lester Bowles", Encyclopedia Canadiana, vol. 8, Ottawa, 1972, Grolier, 135.

- ↑ Shadow of Heaven: The Life of Lester Pearson, volume 1, 1897-1948, by John English, Vintage Publishers, 1989.

- ↑ Mr. Prime Minister 1867-1964, by Bruce Hutchison, Toronto 1964, Longmans Canada publishers.

- ↑ Citizen of the World: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, volume 1, by John English, Toronto 2006, Knopf Canada publishers.

- ↑ http://ms.radio-canada.ca/archives/2002/en/wmv/autopact19650107et1.wmv

- ↑ Staff. "The Week", National Review, December 23, 2002. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ The View From Out There (washingtonpost.com)

- ↑ "Strong exports to the United States resulting from the mounting demands of the war in Vietnam, combined with a booming domestic market, made 1966 a year of impressive economic growth for Canada." Britannica Book of the Year: 1967, Chicago 1967, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 191.

- ↑ PRESIDENTIAL VISITS WITH HEADS OF STATE AND CHIEFS OF GOVERNMENT

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Elliot Lake". Cityofelliotlake.com. http://www.cityofelliotlake.com/civiccentre.html. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ http://archive.gg.ca/honours/search-recherche/honours-desc.asp?lang=e&TypeID=orc&id=2235

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ "Honorary Degree Recipients". Library.rochester.edu. 2007-02-22. http://www.library.rochester.edu/index.cfm?PAGE=1702. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ "Bates College | Honorary Degrees, 1950-59". Bates.edu. http://www.bates.edu/x61666.xml. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "Princeton - Honorary degrees Awarded". Princeton.edu. http://www.princeton.edu/pr/facts/honorary/#50. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "University of British Columbia Library - University Archives". Library.ubc.ca. http://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/honchron.html. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "Honorary Graduates of Memorial University of Newfoundland 1960". Mun.ca. http://www.mun.ca/senate/Honorary_Degrees/honorary_degrees.html. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "Johns Hopkins University | Commencement 2005". Jhu.edu. 2004-05-19. http://www.jhu.edu/news_info/news/commence05/honorary/alpha.html. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ [6]

- ↑ http://www.uwo.ca/univsec/senate/honorary_degrees_by_surname.pdf

- ↑ "Office of the President - Honorary degree recipients from 1961 to present". Oldwebsite.laurentian.ca. http://www.oldwebsite.laurentian.ca/president/index_e.php?file=honorary_e. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "UofR General Calendar: The University of Regina". Uregina.ca. http://www.uregina.ca/gencal/gencal1999/uofr_history.html. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "Honorary degree recipients :: University of Saskatchewan Archives". Usask.ca. http://www.usask.ca/archives/history/hondegrees.php?screen=advanced. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "Convocation > McGill Facts and Institutional History > McGill History > Outreach". Archives.mcgill.ca. 2004-03-24. http://www.archives.mcgill.ca/public/hist_mcgill/conv/convocation.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ http://www.queensu.ca/secretariat/HDrecipients.pdf

- ↑ "Dalhousie University". Convocation. http://convocation.dal.ca/history/08_honorary.html. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ [7]

- ↑ [8]

References

- Beal, John Robinson. Pearson of Canada. 1964.

- Beal, John Robinson and Poliquin, Jean-Marc. Les trois vies de Pearson of Canada. 1968.

- Bliss, Michael. Right Honourable Men: the descent of Canadian politics from Macdonald to Mulroney, 1994.

- Bothwell, Robert. Pearson, His Life and World. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1978. ISBN 0-07-082305-7.

- Bowering, George. Egotists and Autocrats: The Prime Ministers of Canada, 1997.

- Champion, C.P. (2006) "A Very British Coup: Canadianism, Quebec and Ethnicity in the Flag Debate, 1964-1965." Journal of Canadian Studies 40.3, pp. 68–99.

- Champion, C.P. "Mike Pearson at Oxford: War, Varsity, and Canadianism," Canadian Historical Review, 88, 2, June 2007, 263-90.

- Donaldson, Gordon. The Prime Ministers of Canada, 1999.

- English, John. Shadow of Heaven: The Life of Lester Pearson, Volume I, 1897-1948. Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1989. ISBN 0-88619-169-6.

- English, John. The Worldly Years: The Life of Lester Pearson, Volume II, 1949-1972. Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1992. ISBN 0-394-22729-8.

- Ferguson, Will. Bastards and Boneheads: Canada's Glorious Leaders, Past and Present, 1997.

- Fry, Michael G. Freedom and Change: Essays in Honour of Lester B. Pearson. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1975. ISBN 0-7710-3187-

- Hillmer, Norman and J.L. Granatstein, Prime Ministers: Rating Canada's Leaders, 2001.

- Hutchison, Bruce. Mr. Prime Minister 1867-1964, Toronto: Longmans Canada, 1964.

- Stursberg, Peter. Lester Pearson and the Dream of Unity. Toronto: Doubleday, 1978. ISBN 0-385-13478-9.

- Thordarson, Bruce. Lester Pearson: Diplomat and Politician. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1974. ISBN 0-19-540225-1.

Writings

- Pearson, Lester B. Canada: Nation on the March. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1953.

- Pearson, Lester B. The Crisis of Development. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970.

- Pearson, Lester B. Diplomacy in the Nuclear Age. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1959.

- Pearson, Lester B. The Four Faces of Peace and the International Outlook. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1964.

- Pearson, Lester B. Mike : The Memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester B. Pearson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972. ISBN 0-575-01709-0 .

- Pearson, Lester B. Peace in the Family of Man. London: Oxford University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-563-08449-9.

- Pearson, Lester B. Words and Occasions: An Anthology of Speeches and Articles. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970. ISBN 0-674-95611-7.

External links

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- "Greatest Canadian" write-up of Lester Pearson

- National Archives biography

- Nobel prize website

- Canadian Peace Hall of Fame

- Order of Canada citation

- Lester B. Pearson - Parliament of Canada biography

- CBC Digital Archives – Lester B. Pearson: From Peacemaker to Prime Minister

- University of Toronto Athletic Hall of Fame, Inducted 1987

- Lester Bowles Pearson from The Canadian Encyclopedia

- An in-depth exploration of Pearson’s diplomacy during the Suez Crisis of 1956

| 19th Ministry - Cabinet of Lester B. Pearson | ||

| Cabinet Posts (1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predecessor | Office | Successor |

| John Diefenbaker | Prime Minister of Canada 1963–1968 |

Pierre Trudeau |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Leighton McCarthy |

Canadian Ambassador to the United States of America 1944–1946 |

Succeeded by H. H. Wrong |

| Preceded by Luis Padilla Nervo |

President of the United Nations General Assembly 1952–1953 |

Succeeded by Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Louis St. Laurent |

Secretary of State for External Affairs 1948–1957 |

Succeeded by John Diefenbaker |

| Preceded by Louis St. Laurent |

Leader of the Opposition 1957-1963 |

Succeeded by John Diefenbaker |

| Preceded by Thomas Farquhar |

Member for Algoma East 1948–1968 |

Succeeded by none (riding merged into Algoma) |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Louis St. Laurent |

Leader of the Liberal Party 1958–1968 |

Succeeded by Pierre Trudeau |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Jack Mackenzie |

Chancellor of Carleton University 1969–1972 |

Succeeded by Gerhard Herzberg |

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||